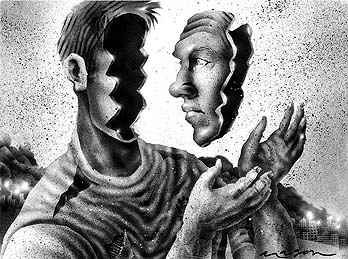

Each of us has a narrator in our head. An internal voice that we call “me”. And most of us assume that this narrator is real. We assume that it’s our true self. Some believe it’s the thing which inhabits the body and the brain rather than something that arises as a result of a body and a brain.

On the nature of self and non-self

Each of us has a narrator in our head. An internal voice that we call “me”. And most of us assume that this narrator is real. We assume that it’s our true self. Some believe it’s the thing which inhabits the body and the brain rather than something that arises as a result of a body and a brain.

Who do you think I am? Who do you think you are? Who were you before you were born? Who will you be after you die? And the most important question of all: how did we become who we think we are? These are among the fundamental questions puzzled over by spiritual seekers for millennia. The Buddha had his own answer to them.

I want to talk about the concepts of Self and non-self: Atman and Anatman. To try to eliminate some confusion with terminology as I go along, when I use the little “s” version of the term self, I am talking about who we think we are based on our perceptions of ourselves that have been created through our experiences in life. This is our ego-self. When I use the term Self (big “S”) I am talking about the essence of who we are independently of who we think we are. Big-S Self is the experience of our True Nature, our Buddha Nature. In Buddhist and Hindu literature, Self (big S) is referred to as Atman, the universal consciousness, and Anatman is referred to as the experience of non-self – non-individual-self that is.

I’ve written in the past about various Buddhist concepts and how they relate to (or in many cases, counter) the Western religious concepts that many of us were raised on. None of these concepts was as important and integral to the Buddha’s teaching as the truth of Anatman: non-self. In my book, Zen Meditation and Wisdom for a Better Life, I briefly touched on ideas regarding the early stages of development of the ego-self when we are young children but I’d like to look a little bit deeper into the development of ”self” awareness before I talk about it’s fundamental illusory nature and the liberating experience of non-self.

First consider this question: is the self the base entity that has thoughts, feelings, beliefs, memories, and relationships? Or, is the self a result of all these other things (thoughts, feelings, beliefs, memories, and relationships)? The self arises as a result of thoughts, feelings, memories, relationships, and so on. To illustrate with an analogy, think of a church. We don’t say that there is a church as a base entity and it has members, buildings, chairs, values, and so on. Rather, we say that the sum of those things make up the church. Neuroscience has demonstrated repeatedly that there appears to be no center of self in the brain, but rather there are many processes that come together to create the sense of a self. [See, for example, Faces and ascriptions: Mapping measures of the self, by Dan Zahavi and Andreas Roepstorff in Consciousness and Cognition, Vol. 20, Issue 1, March 2011, pp. 141-148.]

So that brings us to another very important question – it has been important to spiritual seekers of all times and traditions. The question is this: is the “self” a real entity? We clearly have an idea of who we are, we feel that we are separate individuals and that that individuality is defined by our unique self. So yes, self is real, we say. But as soon as we try to define it, to fix it, it gets as slippery as hot oil on a skillet. When we look into the nature of who we are as an individual being, we find that we simply cannot come up with any fixed answer. Who we are as individuals has changed over the course of our lives, not only in terms of how we think about things, but by what we believe and don’t believe as well. In fact, all of our cells die off and new ones take their place … this happens all the time. We have a sense that we are a fixed identity, that our self is real … but is it? In Buddhism we say that this identity-self is mere illusion, Maya. An illusion is real though, as an illusion, but that’s it. Looking at a painting of a flower we know we’re looking at a painting, not a real flower.

The self is in a constant state of flux and is ever-changing. We say that we can never step into the same river: so it is with the self. We can never experience the same self in any two moments although the sense of self gives the illusion of continuity. Just as physicists recognize that we alter the outcomes of the material world around us simply by the act of observing it, so do we continuously recreate the self by searching for it, studying it, and thinking about it: by interacting with our environment, of which our brains are integral parts. As humans, we become the stories that we tell about ourselves.

I want to tell you what the Buddha had to say about self and “Non-Self”. The Buddha believed that the illusion of a permanent and separate self was one of the primary problems that caused the suffering he wanted to eliminate in human beings. Near the end of his life he is said to have said: “Birth after birth I have searched and wandered with no reward and with no rest seeking the house-builder. Birth is painful – again and again; House-builder! You are seen! You will not build a house again. All your rafters are broken, your ridge pole dismantled. Immersed in dismantling, the mind has attained the end of craving”. The “house-builder” that the Buddha spoke of is that which causes us to compile thoughts, ideas, experiences, relationships, and other phenomena of the mind into a permanent and separate self. Through the Buddha’s years of searching and engaging in every known variety of spiritual practice available to him at the time, we are told, he came to discover for himself that the house-builder was not a real entity and this knowing shattered forever what he called the “round of rebirths” [which need not be interpreted as reincarnation – but as our continual process of redefining our ever shifting notion of self].

He describes this in more detail in a dialogue with monks which was later written down in what became known as the Anātmalakṣaṇa Sūtra :

"Monks, form is not-self. If form were self, then this form would not lead to affliction, and one could say of form: 'Let my form be this and not that.' And since form is not-self, it does lead to affliction, and none can say of form: 'Let my form be this and not that.'

"Monks, feeling is not-self for the same reasons, also perception, determination, and consciousness are not-self.”

"Tell me Monks: is form permanent or impermanent?" — to which the monks replied "Impermanent, Lord." — "Now is that which is impermanent painful or pleasant?" — "Painful, Lord." — "Now is that which is impermanent and subject to change fit to be regarded as 'This is mine, this is I, this is my self'"? — "No Lord."

"Ask the same of feelings, perceptions, determinations, and consciousness.”

"So, monks any kind of form whatever, whether past, future or presently arisen, whether gross or subtle, whether in oneself or external, whether inferior or superior, whether far or near, must with right understanding how it is, be regarded thus: 'This is not mine, this is not I, this is not myself.'

"Any kind of feeling, perception, determination, or consciousness whatever, whether past, future or presently arisen, whether gross or subtle, whether in oneself or external, whether inferior or superior, whether far or near must, with right understanding how it is, be regarded thus: 'This is not mine, this is not I, this is not myself.'

"Monks, when one has heard (the truth) sees thus, he finds estrangement in form, feeling, perception, determinations, and consciousness.”

"When he finds estrangement, passion fades out. With the fading of passion, he is liberated.”

For the Buddha, the self was not permanent, not separate, and not identifiable as a thing in and of itself.

There are varying levels of information that make up our sense of self. There is consciousness, which includes that narrator that I mentioned earlier. There is pre-consciousness, which includes all the stuff we can recall if we try. And there is a collection of information in the non-conscious mind, sometimes referred to as the Adaptive Unconscious or, in Buddhist terminology, “Alaya Consciousness”. People throughout history have debated the nature of each of these storehouses of information as well as the degree to which we can access each through some practice or another. At the level of consciousness things like our current experience and our current thoughts exist--obviously a very small portion of our selves. At the level of pre-consciousness lies the stuff that we can fairly easily recall such as the names of our past teachers, first loves, streets we grew up one and so on. But the stuff that really makes up most of who we think we are, it seems, lies at the level of non-consciousness and much of it we may never be able to dig up and bring to the level of consciousness. However we may be able to get clues and infer certain things about the contents of our non-conscious mind if we really want to.

One of the most important things I have learned from practice and study is that we cannot ever hope to fully understand the working and the contents of our non-conscious mind and sometimes we get ourselves into trouble when we try too hard. For example, if we try to analyze all the underlying reasons why we love someone we may convince ourselves that we know all the reasons or we may actually make ourselves start to second guess whether or not we really do love that person. I read a book that talked in part about a study where people were asked to list the reasons why a relationship was either going well or not going well and another group was asked to state whether their relationship was going well or not but without analyzing reasons for it. The group that did not analyze reasons was more accurately able to describe how the relationship was going. The analyzing group had constructed theories about why the relationship was going well or not well based on assumptions and constructed stories based on partial (often faulty) data that they were trying to access from their non-conscious mind. As Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once said “He who deliberates lengthily will not always choose the best.” Poker players have a more simple motto: “Think long, thing wrong”. For more on the idea that sometimes overanalyzing isn’t the most accurate way to solve problems, I suggest three books; one is called Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell, the second is Sway: The Irresistible Pull of Irrational Behavior by Ori Brafman and Rom Brafman, and finally, Strangers to Ourselves by Professor Timothy D. Wilson.

There is an abundance of information stored in the non-conscious mind that we can generally not access, which guides much of who we become from moment to moment and from year to year throughout our lives. Some examples of the information from the non-conscious mind might be prejudices, fears, motivators, and values. We have these underlying drivers of our behavior but we are generally not aware of them and usually do not understand that they guide the decisions made in our consciousness and our pre-consciousness. But where did the information in the non-conscious mind originate? I don’t accept that “God” programmed the information onto my non-conscious mind, so I have to assume that it is there as a result of primarily two causes; the evolution of our species and all the changes our species has gone through over thousands of years, and the very early information that my parents and early caregivers imparted to me before I was aware that I was receiving information at all; in other words, nature and nurture.

My body and my brain have both evolved from earlier, more primitive creatures; for example, the human brain stem is the part of the brain that controls breathing, heartbeat, hunger, fight or flight response, and sex drive, which is basically all that was required of our very earliest ancestors. Then grafted onto this brain stem we evolved our ever increasing levels of additional brain structures that give us the ability to perform increasingly higher thought functions up to and including that which we are doing right now. I can deduce that some of “who I think I am” is a result of the most basic level of brain activity – I want food when I’m hungry and I fear dangerous things at appropriate times. However part of that which makes me uniquely “me” can also be attributed to things that were taught to me at the earliest stages of my development as a separate human organism by my parents and caregivers; for example I have a decent sense of fairness, kindness, and respect for life that were probably imparted to me by my mother and father before I had language skills or a sense of self. If my parents had been bad people instead of good people, I surely would have turned out differently. On and on this development went and still goes today as I meet new people, have new experiences, and create new narratives in each moment of every day.

Ultimately, the point is this: The self is made of non-self processes. I am not me and you are not you; at least not in the sense that one usually applies the terms “me” and “you”. We are products of others and of the past. I am each of you and I am everyone and everything that I have come into contact with in the past, which includes the recent past of my physical body but also the distant past of previous lives; lives which I can neither label as “mine” or “not mine”, but which are part of me through genetic evolution. This means that in order have an idea of who I am as a unique individual, I need to look both inside and outside. I need to draw up a narrative based on what I can access and what I can infer about the various levels of my consciousness and I need to look out at everyone in my environment. Only when I consider all of this can I begin to understand just who I am—who I think I am, that is. But I will surely be someone else tomorrow.

Knowing this, as many of us do, why do we still act selfishly? Knowing this, why do we not care for each other and treat each other with the respect deserving of all human beings? Is knowing that we create ourselves with our very thoughts, actions, interactions, and relationships, enough to allow ourselves to act with love and compassion for one another? It seems not. Awareness of non-self, Anatman, must be awakened directly, intuitively – we must come to see ourselves as something other than individual separate beings, to see our formerly perceived ego-identity as a phantasm, and that can only happen by delving deeply into the nature of being itself—and this is what the Buddha was famous for, and what he spent the last years of his life encouraging people to do. We cannot discover the Self (big S) by studying the nature of the self (little s). It is only through spiritual disciplines such as meditation and contemplation that insight into Ultimate Reality, into our true nature, happens.

And it all starts from a very simple question: "Just who am I?"