In her bestselling spiritual memoir "Eat, Pray, Love", Elizabeth Gilbert tells a delightful story of a great Hindu teacher who led his followers in daily meditation in his ashram. The only problem was that the teacher "had a . . . cat", an annoying creature, who used to walk through the temple meowing and purring and bothering everyone during meditation. The solution that the teacher came up with was to tie the cat to a pole outside during meditation times to allow everyone to sit undisturbed by the feline intruder. This became a habit and, over the years that followed, into a ritual. Without the the cat tied to the pole in front, no one could sit. Inevitably, once the cat died the ashram was thrown into a serious spiritual crisis!.

Every religion has its rituals, some emerging from everyday life, like the cat tied to the pole. Others seem, from today's perspective, to be the result of conscious design (the Roman Catholic Eucharist or our own ubiquitous Incense Burning). Even such things as the design of our robes and the sequence of our Koan study can be objects of intense spiritual meaning and attention. To those of us who are lighting the incense or meditating on a particular koan or doing our 100,000th prostration or repeating a well-worn and often repeated mantra, these rituals can be of tremendous importance. We accept that they are, for us, a step on the path to enlightenment. Without them, we feel spiritually adrift, floating aimlessly in the sea of nothingness.

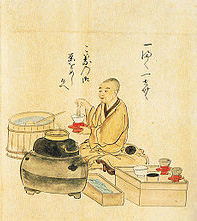

Many of us have our favorites: daily chanting of the Heart Sutra, of Hakuin's Song of Zazen; lighting incense at an altar in our home, in a temple, or in a monastery; group walking meditation between sitting sessions; Oryoki during meals; striking the wooden fish during chants; the sound of the bowl being struck at the beginning and end of zazen. Many zen practitioners have very personal rituals that we repeat whenever we sit on a cushion to meditate. Do all of these have real meaning? The obvious answer is that of course they do, or there would be no reason to act them out. Without this personal meaning, doing these things -- even shared and performed simultaneously with many others -- would be no more than an exercise in absurdity.

In fact, many of the Zen masters of our long history have recorded the impromptu encounters of master and student, gathered these stories and insisted that students study them for their depth of meaning and insight. In the repeating of these koans and in the frequent revisiting of them, we have ritualized the spontaneous; another Zen paradox!

So what's the catch? These rituals are important, but they have no intrinsic or inherent meaning. They inherently have no more meaning than if we were to spontaneously shout in joy or in agony when we first walk into a temple. They are meaningful only because we attribute meaning to them. Like so many other things we experience, the true meaning of these actions and of the repeating of sutras, poems and songs is within our "Buddha Mind". They have no absolute meaning. And for Zen practitioners, the search for meaning in our rituals is complicated by the equally compelling search for meaning in our everyday activities. How can we say that chanting sutras is more meaningful than chopping carrots for a shared meal, than sweeping a courtyard after a windstorm, with shoveling snow on a cold winter morning, or with tending the sick and dying when there is no one else to do the task? If we are conscientious in our practice of mindfulness they are, in fact, the same. When we decide each and every one of our actions is, in turn, both spiritually significant (we might even say, "holy") and mundane, we are able to live in the moment. For a Zen practitioner, meaningful ritual becomes undistinguishable from the mundane activities of everyday life and, at the same time, the commonplace actions of human existence become as sanctified as ritual.

Its all in our mind.