Students who come to my weekly Dharma talks (or who meet regularly with me in private) are often confronted with my insistence that they view the world more holistically. This is typically triggered by one or more meetings in which claims are made that a “big picture” perspective is fine philosophically, but typically has little relevance to one’s personal suffering. “How does the structure of the universe or what is happening half way around the world have to do with me or my situation?” The answer is obvious and simple, but its very simplicity leads people to view the answer as being overly simplistic and, therefore, not acceptable. But the truth is: when one’s worldview is small, the small problems of life seem quite significant, and when one’s worldview is large, even the larger problems of life seem to become quite trivial. We have the choice of viewing the world either way, and how we respond or feel is based on which perspective we choose to take.

Students who come to my weekly Dharma talks (or who meet regularly with me in private) are often confronted with my insistence that they view the world more holistically. This is typically triggered by one or more meetings in which claims are made that a “big picture” perspective is fine philosophically, but typically has little relevance to one’s personal suffering. “How does the structure of the universe or what is happening half way around the world have to do with me or my situation?” The answer is obvious and simple, but its very simplicity leads people to view the answer as being overly simplistic and, therefore, not acceptable. But the truth is: when one’s worldview is small, the small problems of life seem quite significant, and when one’s worldview is large, even the larger problems of life seem to become quite trivial. We have the choice of viewing the world either way, and how we respond or feel is based on which perspective we choose to take.

My talks are often received as flights of fancy, addressing vast, over-arching topics that seem as distant and irrelevant as the galaxies I use as examples. But in reality, the vast, over-arching principles really are the most relevant. Once a person recognizes this and begins to perceive the world from this larger “grand plan” perspective, he or she will begin to notice that so much of the minutia of daily life becomes wholly insignificant. We discover that the real issue is that we take our problems and ourselves far too seriously, and that if we begin looking at the “bigger picture” the very same life becomes much less troublesome.

In my work as a craftsman, I often make numerous mistakes on any given project. As each mistake occurs, I curse under my breath and begin to fret on how I am going to deal with such an obvious blemish. A nick here, a scratch there, accidently painting over the line and forgetting to clean off the glue . . . all seem to be major mistakes when I am in the process, but when the boat is finally finished, where are all the mistakes? Every beautiful yacht can either be seen as a masterpiece of craftsmanship or a sorry aggregate of countless mistakes. Our lives are really no different - we can view ourselves and our life situations as “a sorry aggregate of countless mistakes” or as masterpieces of biological craftsmanship. It all depends on how closely we look at the picture.

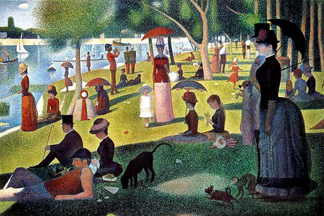

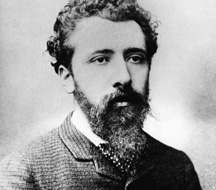

The painting above, entitled Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, was painted over a two year period (1884-1886) by French artist George-Pierre Seurat. The painting is 10 feet wide and is painted entirely in tiny dots applied one dot at a time with a pointed detail brush. This technique, which became known as Pointillism, is basically the way all illustrations and published photographs are printed today. Modern computer printers (and even your computer monitor) use this same technique to present to your eyes the image you see.

The painting above, entitled Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, was painted over a two year period (1884-1886) by French artist George-Pierre Seurat. The painting is 10 feet wide and is painted entirely in tiny dots applied one dot at a time with a pointed detail brush. This technique, which became known as Pointillism, is basically the way all illustrations and published photographs are printed today. Modern computer printers (and even your computer monitor) use this same technique to present to your eyes the image you see.

In this painting - there are no blends, no solid fields of color - just dots! Primary colored spots that have been strategically placed to produce the overall effect of a single picture. So where are the mistakes? Surely if we look closely we can find them. A red dot accidentally placed where a yellow dot should have been, or maybe some dots that are too close to other dots and maybe even accidently touching. Seurat was just as human as any of us and probably grieved at every dot that didn’t land on the canvas exactly as he had envisioned. How many did he wipe off or paint over with an alternate color? Or how many did he just say “Oh well” and move on to the next? Surely, on a six-by-ten foot painting of over eight hundred sixty four thousand dots, there must have been countless mistakes of misplacement and/or color selection. But when the painting was done, it instantly became a timeless masterpiece of impressionist art. How did this happen?

The answer is simple: the over-arching principles are more significant to the outcome of the “big picture” than any of the individual events. In the big picture the laws of probability and statistics prevail. At first, this may seem impersonal and suggest the existence of a cold and uncaring universe, but in reality, the opposite has proven true. Every physical system - from the grand scale of the universe to the field of quantum mechanics - has proven to be exactly what is necessary for our human existence and survival. This includes our abilities to reason, use abstract thought, make art and have human feelings like love and compassion.

Typically the bulk of what causes our mental anguish is looking at our situation from the wrong perspective. We are notorious for looking at things too closely and taking them too personally when a broader perspective would not only give us a clearer picture, but also greatly diminish our personal anxiety. If we were to walk up toSunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte and fix our gaze about three inches from the canvas, we would probably see a real mess! Dots of random color, size and placement just scattered randomly with no apparent rhyme or reason. Who could possibly call this art? But step back a bit and one begins to see that it all makes perfect sense. From the correct perspective and scale it not only makes sense, but becomes pleasing to our artistic eye. It becomes art depicting life.

Typically the bulk of what causes our mental anguish is looking at our situation from the wrong perspective. We are notorious for looking at things too closely and taking them too personally when a broader perspective would not only give us a clearer picture, but also greatly diminish our personal anxiety. If we were to walk up toSunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte and fix our gaze about three inches from the canvas, we would probably see a real mess! Dots of random color, size and placement just scattered randomly with no apparent rhyme or reason. Who could possibly call this art? But step back a bit and one begins to see that it all makes perfect sense. From the correct perspective and scale it not only makes sense, but becomes pleasing to our artistic eye. It becomes art depicting life.

This piece of art depicting life is not just a picture of a day in a park, but also a striking example of how seemingly random, unconnected dots can make up the entire picture. Our entire universe is structured exactly like this. Atoms, which are made of unconnected particles, make up molecules, which are unconnected particles that ultimately become stars and galaxies that are also rather random and vastly separated. These “dots” in space and time, and at every scale, show us that while things, looked at closely, seem to be random and disconnected, they are actually connected by space and time and are all required to make up the “big picture”.

Our lives, living at this human scale, are no different - everything close-up seems to be independent and disconnected, but from a different perspective our lives become an obvious continuity. The appearance of each of us being separate individuals is no less real than the appearance of individual atoms when something is viewed at high magnification – but take away the electron microscope and how does it look? The multitude of atoms merges into a single object at a larger scale. Like the atoms, we each have our own “space” and we see ourselves as independent entities, but from a biological or sociological perspective we are simply part of a larger group which in turn is part of yet another larger group.

As long as we limit our understanding of who we are to our own “space”, we can see everything around us as being something other than us; but as soon as we begin acknowledging the other things that sustain us, we begin to see the illusionary state of our imagined singular existence. Beginning with the air we breathe and the water we drink, we begin to recognize that we are totally dependent on the existence of “things other.” The apple we ate for lunch is not something separate from ourselves but the very stuff from which we are made. Although it may sound corny when it comes to our physicality, we actually are what we eat.

Genetically, we are a magical blend of components inherited from our ancestors, who become total cognitive strangers after only a couple generations. We do not see ourselves as continuations of them, let alone as continuations of the entire race called ‘humans’, or the entire mammal branch called ‘primates’. Every so-called ‘individual’ represents a dot in the mural of our existence - close up we see them as separate, but step back and they are just a portion of a bigger picture. When the biological puzzle is finally pieced together we discover what John Muir meant when he said: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

This all being said, there are still those who will ask: “This is all well and good, but what does it have to do with me or my situation? How do we apply all this fanciful idealism or scientific trivia to our real life situations? How can accepting broad-stroke theories of existence help to relieve my suffering?” The reason these questions remain is because they have simply failed to step back and look at the bigger picture. Still looking at the painting from three inches away, all they can see is a mess; a random scattering of disjointed objects and events that appear to have nothing in common.

We have all seen this in other people - friends and relatives that fail to see their situation as being self-imposed and self-limiting. Their attitudes about, and relationships with, family, friends, people, work, food, drugs, politics and the environment, all paint a pretty clear picture of why they are experiencing their life as unfair or unjust. However, through their denial of the big picture, they somehow see themselves as disconnected from all the commotion. We say that “They are their own worst enemy.”

But what about ourselves? Who is the cause of our suffering? Are we our own worst enemy? And if so, what is the root cause? From a wider perspective, we see our friend’s problem as obvious and self-imposed, but from the center of our own personal storm, we suffer from the very same lack of perspective. Instead of seeing our situation in its holistic context, we only see ourselves as separated and suffering. We see ourselves as the misplaced dot in an otherwise complete picture of the universe, where everything else is just as it should be.

In order to rectify this situation, what we need to be able to do is step back and look at our lives from a different perspective. This may require looking at ourselves in the same distanced way that we look at other people and their “issues”. This isn’t easy, because we tend to take our own lives personally and feel confined to this personal perspective. But the truth is that we are perfectly capable of looking at our own situation from a more holistic perspective. We can look at our own lives as if we were someone we know, rather than someone we are. For the most part, when we look at the bigger picture, we will find that we are fairly generally in the center of the graph, just about average in just about every way. We usually discover that, overall, we really are no better off or worse off than other people that we know and compare ourselves to. Where we might find ourselves deficient is usually matched up with other peoples’ alternate deficiencies fairly equally.

Again, this can be observed at different scales and seen in a more holistic perspective. If we want to compare our lives to others’, we should be looking at the whole picture - not just our current situation - and work from a large sampling of “others” - not just a particular someone we have picked as some arbitrary standard. For example, if you are a “Middle Class, Working American”, your comparisons should be to the full range of what constitutes “Middle Class, Working Americans”. Not just the top half, not the median, but the whole sample. This sample should also include all considerations of conditions over time, maybe a lifetime. For example - you may currently be unemployed, so your sampling should include the understanding that nearly everyone in your sampling has probably been unemployed at one time or another in their lifetime.

However, if that scale doesn’t work for you maybe you should go one step further. How does your life compare to the world population of seven billion? Keep in mind that these suggestions are just examples; the actual scale you select may or may not be the right one. However, if you find that you land well within the “bell-curve” of any particular scale sample, things probably are just as they should be. For example, select any dot in Seurat’s painting and say that is your dot in the big picture. How does it compare with all the other dots? Bigger than some, smaller than others, more round than some, more irregular than others, yellow instead of blue, but the same yellow as all the other yellow dots - is this any better or worse than any other dot on the canvas? This comparing ourselves to dots on a painting is not to belittle or dismiss our existence as trivial, but rather to point out that our current concerns are usually trivial when held up to the “big picture” of our lives.

Like everyone else, my own life has been filled with ups and downs. I’ve had my share of losses and gains, good times and bad times, long periods of good health, plenty of times with severe illness, times of sheer terror and times of absolute joy. So using my own life (which means all of it) as the scale, what’s the score after 50 or 60 years? Well, I’m still here and experiencing my life as it continues to happen. Life in general is pretty good despite all the negative things mentioned in the first part of this paragraph. When I look at my whole life as the painting, the dots that represent the health issues I’m experiencing at this moment seem quite trivial. When I compare my life with the large number of people I know in my demographic profile, I find myself even better off than I thought. When I compare myself to middle aged men world wide, I see that life really couldn’t get much better. So I ask myself - what’s all this fuss about?

I have found that by looking at the bigger picture and looking at my situation as objectively as possible, I really can distance myself from my limited point of view and see things from a larger perspective. The more I do this, the better I get at doing it. In fact, it has even gotten to the point where I look at the big picture immediately and manage to skip right over all the “why me?” or “poor me . . .” thoughts altogether. Sometimes, when everything seems to be going wrong, I find myself comparing my situation to a slapstick comedy and it makes me laugh. The improbability of having just about everything going awry at the same time just becomes funny. And then I remind myself of those times when everything went “perfectly” even when the odds were against me, and I laugh again.

Regardless of how we feel at the particular moment, if we were to consider this moment as a dot in the painting, how would it compare? If the painting of our lives were painted with blue dots when sad, red when angry, yellow when happy, green when healthy, violet when sick etc… what colors would dominate our picture? Would the healthy green dots outweigh the sickly violet ones? Would yellow dots out number blue? Keep in mind that “happy” would be the same as feeling okay or just normal - that’s what happiness actually means: okay with what’s “happening”.

There is a term used by planners and environmentalists which is a perfect example of living life from a larger perspective: Think globally, act locally. Thinking globally is thinking holistically, acting locally is thinking/acting/living from this big picture perspective. Those of us who have taken this philosophy to heart have found that it really does make us feel better about ourselves when it comes to issues like the economy and the environment. This approach also works from any individual perspective at any given scale. We could consider our “globe” as the universe, the planet, our sphere of influence, our lifetimes or our bodies - it really makes no difference. An example of this might be where we think of our lives as the “globe” and eating healthily; whereby we want to satisfy our current hunger by eating something (acting locally) but instead of eating junk food we choose to have a healthy meal in order to preserve our long time health (thinking globally).

If we keep this perspective of thinking globally and acting locally in the forefront of our minds and learn to continually apply this logic to our lives, we will discover that our lives will generally improve over time. Not only will they improve in the way of attitude and well being, but in our physical environment as well. Whether we view our physical environment as the planet, the neighborhood, or our workplace makes no real difference. Our environment is where we live, and where we live is still where we live no matter which scale we choose.

However, if we forget to think “globally” we will discover that “locally” really cannot fare so well in the long run. We must remember that any scale, whatever we are looking at, is only part of a larger picture, and until we learn to connect the dots, we will continue to suffer from our limited perspective (i.e., ignorance). The universe is a big place and our consciousness resides at its very center, with everything we know of existing within this infinite series of concentric spheres. Some spheres are so small that we tend to doubt their significance and others are so large that we cannot even comprehend their importance. But they all represent our personal environment, at the center of which lives the living, breathing “dot” of awareness that every single one of us refers to as “me.”